Football fans, like any gamblers, are pretty well guaranteed to endure more bad days than good ones. Liverpool supporters, to take a high‑achieving example, probably feel their domination of the 1980s was several lifetimes ago. Faithful Terriers must scarcely believe there was a time when Huddersfield Town were the powerhouse of English football, becoming the first team to win the league on three successive occasions in the 1920s.

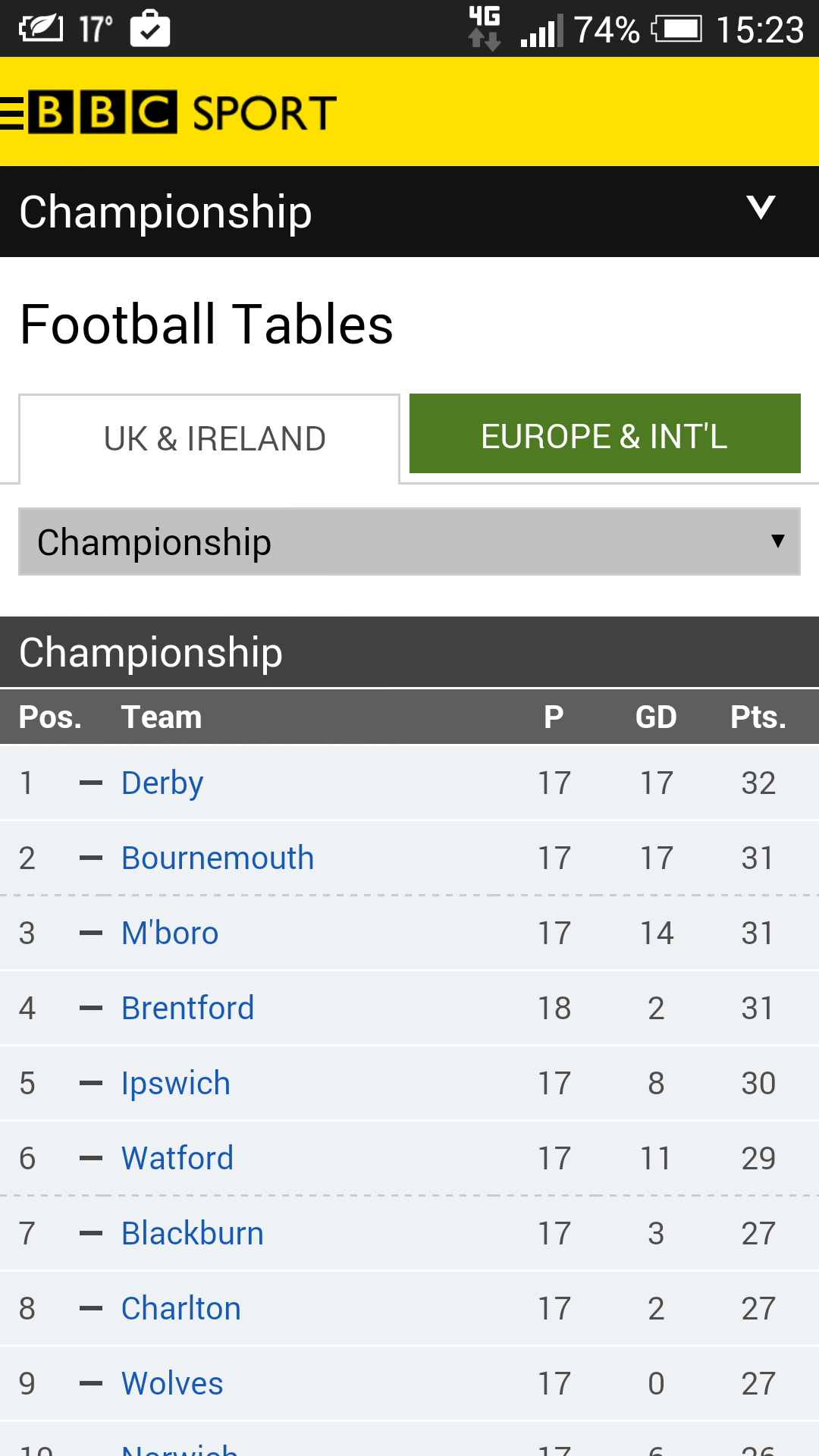

But spare a festive thought for the long-suffering followers of Brentford, a club who celebrated their 125th birthday in October. Brentford have won a couple of minor trinkets in that time but really nothing to build even a very tiny cabinet about; their heyday came with a pair of top-six finishes in the old First Division in the 1930s. And then imagine how good it must feel to be a Bee right now. After knocking around in the lower leagues for ever, Brentford have embarked on a run that – precisely halfway through the campaign – took them to third in the Championship, before Boxing Day’s slip-up at home to Ipswich. Losing 4-2 was a setback but it was against one of the two teams ahead of them; it is suddenly conceivable that next season the team will contest a west-London derby against Chelsea in the Premier League.

Brentford, new boys in the Championship this year, were not expected to be at this end of the table. This time last year, Wigan Athletic poached their dynamic manager, Uwe Rösler, who was credited with introducing the team’s attacking, high-tempo style. Rösler was replaced internally, by Mark Warburton. The sporting director was not a sexy appointment, which is another way of saying that he’s a bald, middle‑aged man from Enfield – but he’s very New Brentford. Never much of a player, Warburton became a currency dealer in the City in the 1980s, working for companies such as Bank of America and AIG, and turning out at right-back for non-league Boreham Wood on the weekends.

After two decades of waking up at 4.32am five days a week, his mortgage paid off, money in the bank, he decided to get back into football. His education began by spending a year travelling round Europe on his own buck seeing how coaches did it at Sporting Lisbon, Ajax, Barcelona and Willem II.

At the risk of oversimplifying his pan-continental quest, Warburton learned that the best clubs invest in nurturing their young players. He was also impressed that Barcelona’s academy boys asked for a broom and left the changing rooms spotless after matches. As the Brentford manager, Warburton has remained loyal to the squad he had brought through with Rösler and supplemented them with smart investments, such as the top scorer, Andre Gray, and the Spanish playmaker Jota, and canny loan signings, notably Spurs’s Alex Pritchard. (Rösler, meanwhile, was fired by Wigan last month.)

Warburton is the public face of New Brentford, but the vision and the pockets belong to the club’s owner, Matthew Benham. I first heard of Benham when I interviewed Marcus du Sautoy, a professor of mathematics at Oxford University and an Arsenal obsessive, for an Observer article on the data revolution in football. Du Sautoy and Benham studied physics together, and after university Benham went to work in the City for a hedge fund. He got bored with that and – despite having placed only a few bets in his life – he became a full-time gambler. He did well enough to set up a company, Smartodds, which sells statistics and tips to professional gamblers, and that in turn did well enough that in 2012 he bought Brentford, the team he has supported since childhood.

Benham immediately invested £15m and pledged another £10m for a new stadium. Lower those eyebrows; this is not exactly a straightforward case of a rich investor fast-tracking a club to short-term success. Benham appears to be smarter and more sensible than that. On the evidence, what’s happening at Brentford now – stealthily, unbelievably, unfashionably – could be a lesson to which the rest of football should pay attention.

The conclusion of my article on the role of computer analysts in football – I’ll save you 10 minutes, here – was that nobody knows anything. Or perhaps they do, but they are not going to tell you. The field is new and impenetrably secretive, as every club try to squeeze a competitive advantage from the statistics. Benham isn’t much help, either, as he rarely gives interviews.

From public pronouncements it is possible to work out core elements of the Brentford philosophy. Warburton clearly wants to reduce the number of talented teenagers who are lost and discarded in the youth ranks. In September 2013, the club’s academy began a partnership with Uxbridge high school, rated outstanding by Ofsted, that allows them to supervise boys all day, every day, both physically and with their education. The stated aim is to mould them as individuals as much as players – expect freshly swept, Barcelona-spotless dressing rooms – and to have four or more boys make the first-team squad in the next few years.

These individuals will be supplemented by underappreciated signings from outside the club, identified by scouting and data analysis. This is the fabled Moneyball-isation of football and will be overseen by Warburton, Benham and Brentford’s new sporting director, Frank McParland, formerly director of Liverpool’s academy, where he brought Raheem Sterling through after his signing as a 15-year-old from QPR. Benham’s quirky algorithms, honed as a gambler and at Smartodds, may already be paying dividends here, but don’t expect him to ever admit it.

Most of all, as shown with the departure of Rösler, no individual is bigger than the club. Brentford under Benham have a belief in how football should be played and a long-term plan on how that will be accomplished. Even if they could have José Mourinho as their manager, you suspect they wouldn’t want him. It’s a clever strategy and if Brentford, the perennial underachievers, do end up in the Premier League one day soon, then you suspect the only people who won’t be surprised will be the people behind it.

Saturday 27 December 2014 18.00 GMT

Football fans, like any gamblers, are pretty well guaranteed to endure more bad days than good ones. Liverpool supporters, to take a high‑achieving example, probably feel their domination of the 1980s was several lifetimes ago. Faithful Terriers must scarcely believe there was a time when Huddersfield Town were the powerhouse of English football, becoming the first team to win the league on three successive occasions in the 1920s.

But spare a festive thought for the long-suffering followers of Brentford, a club who celebrated their 125th birthday in October. Brentford have won a couple of minor trinkets in that time but really nothing to build even a very tiny cabinet about; their heyday came with a pair of top-six finishes in the old First Division in the 1930s. And then imagine how good it must feel to be a Bee right now. After knocking around in the lower leagues for ever, Brentford have embarked on a run that – precisely halfway through the campaign – took them to third in the Championship, before Boxing Day’s slip-up at home to Ipswich. Losing 4-2 was a setback but it was against one of the two teams ahead of them; it is suddenly conceivable that next season the team will contest a west-London derby against Chelsea in the Premier League.

Brentford, new boys in the Championship this year, were not expected to be at this end of the table. This time last year, Wigan Athletic poached their dynamic manager, Uwe Rösler, who was credited with introducing the team’s attacking, high-tempo style. Rösler was replaced internally, by Mark Warburton. The sporting director was not a sexy appointment, which is another way of saying that he’s a bald, middle‑aged man from Enfield – but he’s very New Brentford. Never much of a player, Warburton became a currency dealer in the City in the 1980s, working for companies such as Bank of America and AIG, and turning out at right-back for non-league Boreham Wood on the weekends.

After two decades of waking up at 4.32am five days a week, his mortgage paid off, money in the bank, he decided to get back into football. His education began by spending a year travelling round Europe on his own buck seeing how coaches did it at Sporting Lisbon, Ajax, Barcelona and Willem II.

At the risk of oversimplifying his pan-continental quest, Warburton learned that the best clubs invest in nurturing their young players. He was also impressed that Barcelona’s academy boys asked for a broom and left the changing rooms spotless after matches. As the Brentford manager, Warburton has remained loyal to the squad he had brought through with Rösler and supplemented them with smart investments, such as the top scorer, Andre Gray, and the Spanish playmaker Jota, and canny loan signings, notably Spurs’s Alex Pritchard. (Rösler, meanwhile, was fired by Wigan last month.)

Warburton is the public face of New Brentford, but the vision and the pockets belong to the club’s owner, Matthew Benham. I first heard of Benham when I interviewed Marcus du Sautoy, a professor of mathematics at Oxford University and an Arsenal obsessive, for an Observer article on the data revolution in football. Du Sautoy and Benham studied physics together, and after university Benham went to work in the City for a hedge fund. He got bored with that and – despite having placed only a few bets in his life – he became a full-time gambler. He did well enough to set up a company, Smartodds, which sells statistics and tips to professional gamblers, and that in turn did well enough that in 2012 he bought Brentford, the team he has supported since childhood.

Benham immediately invested £15m and pledged another £10m for a new stadium. Lower those eyebrows; this is not exactly a straightforward case of a rich investor fast-tracking a club to short-term success. Benham appears to be smarter and more sensible than that. On the evidence, what’s happening at Brentford now – stealthily, unbelievably, unfashionably – could be a lesson to which the rest of football should pay attention.

The conclusion of my article on the role of computer analysts in football – I’ll save you 10 minutes, here – was that nobody knows anything. Or perhaps they do, but they are not going to tell you. The field is new and impenetrably secretive, as every club try to squeeze a competitive advantage from the statistics. Benham isn’t much help, either, as he rarely gives interviews.

From public pronouncements it is possible to work out core elements of the Brentford philosophy. Warburton clearly wants to reduce the number of talented teenagers who are lost and discarded in the youth ranks. In September 2013, the club’s academy began a partnership with Uxbridge high school, rated outstanding by Ofsted, that allows them to supervise boys all day, every day, both physically and with their education. The stated aim is to mould them as individuals as much as players – expect freshly swept, Barcelona-spotless dressing rooms – and to have four or more boys make the first-team squad in the next few years.

These individuals will be supplemented by underappreciated signings from outside the club, identified by scouting and data analysis. This is the fabled Moneyball-isation of football and will be overseen by Warburton, Benham and Brentford’s new sporting director, Frank McParland, formerly director of Liverpool’s academy, where he brought Raheem Sterling through after his signing as a 15-year-old from QPR. Benham’s quirky algorithms, honed as a gambler and at Smartodds, may already be paying dividends here, but don’t expect him to ever admit it.

Most of all, as shown with the departure of Rösler, no individual is bigger than the club. Brentford under Benham have a belief in how football should be played and a long-term plan on how that will be accomplished. Even if they could have José Mourinho as their manager, you suspect they wouldn’t want him. It’s a clever strategy and if Brentford, the perennial underachievers, do end up in the Premier League one day soon, then you suspect the only people who won’t be surprised will be the people behind it.